TEACHING STRATEGIES

Collaboration contributes to meaningful learning experiences as it involves the division of responsibility amongst students in order to achieve an intended outcome as well as develop valuable interpersonal and intrapersonal skills (Churchill et al., 2013, Victoria State Government, 2021). Group work is a critical pedagogical technique that assists in strengthening the “community of learners” in the classroom (Mintrop, 2004, p.142). Thus, collaborative learning is a useful tool to simultaneously engage with curriculum content and develop student skills. The AITSL standards considered through its implementation include 1.1, 4.1, 4.2 and 5.1 as students participation is encouraged in an inclusive environment, critical and creative thinking is developed and students are assessed informally in order to appreciate the effectiveness of the strategy (2017).

The teaching strategy, collaborative learning, was implemented in my Year 9 English lesson. Students engaged in a jig-saw group activity in order to become an ‘expert’ on their allocated genre of Greek play before sharing/discussing their findings in smaller groups (Churchill et al., 2013). This task, as a whole, enabled students to develop their contextual understanding before delving into in-depth study within the unit.

Vecteezy. (2022).Teamwork, four stickmen businessmen holding connected team jigsaw puzzle pieces, hand drawn outline cartoon vector illustration.

This was an effective strategy as it involved students developing “interpersonal and small group skills (including leadership, decision making, trust building, communication and management), and group processing” (Kardaleska, 2013, p.55), necessary in order to increase their self-esteem and ability to exude control in student-centred learning environments (Churchill et al., 2013). Through observation, I recognised that students worked well due to being given creative freedom to create their google slides, a fundamental aspect that underpins the Constructivist theory (Vygotsky, 1978). Moreover, whole class presentations work on the mindset that all learners are capable of demonstrating their understanding entirely in a singular form, adopting a ‘one size fits all’ approach (Sizer, 2004). Thus, the effectiveness of this collaborative strategy was illuminated through students working in mixed-ability groups, presenting to their peers in the form of an informal ‘discussion’ rather than a whole group ‘presentation’. I found that this enabled all groups to share their presentations without time being a restriction and catered for students with diverse needs as they were able to reap the benefits of collaborative learning without being overwhelmed by presenting in front of a large group (AITSL, 2017, 1.2, 1.5 and 1.6).

EXAMPLES OF STUDENT WORK

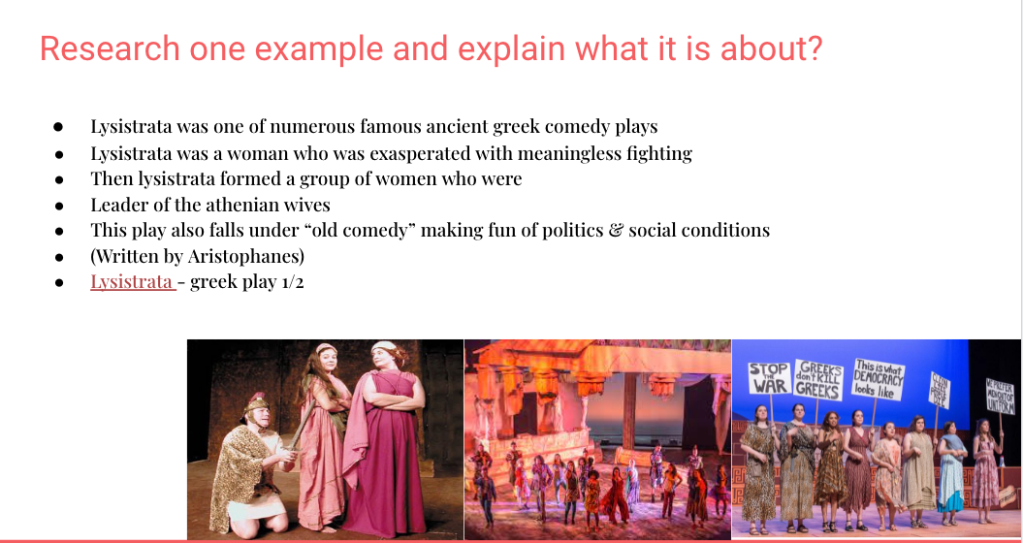

Group 1 – Comedies

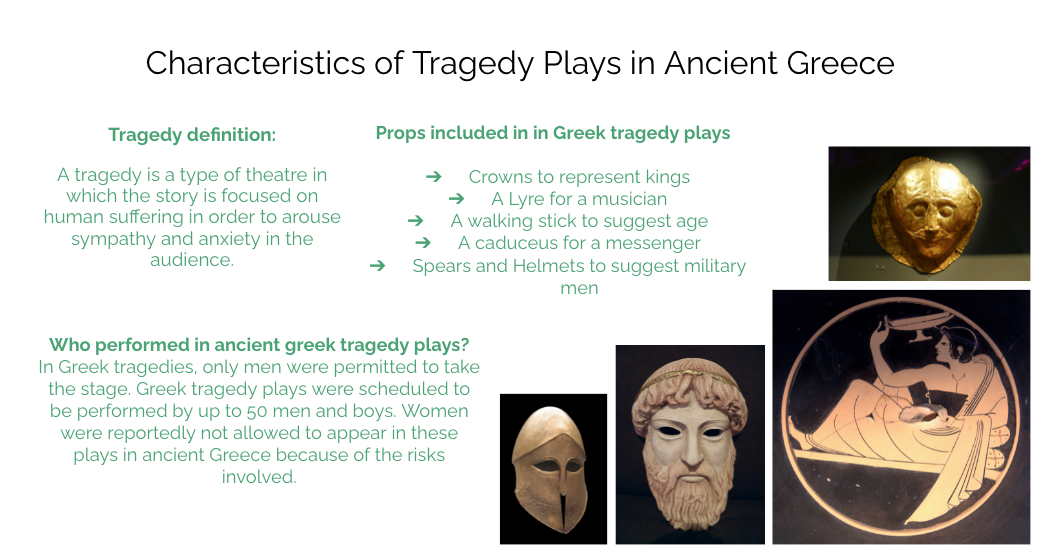

Group 2 – Tragedies

Group 3 – Satires

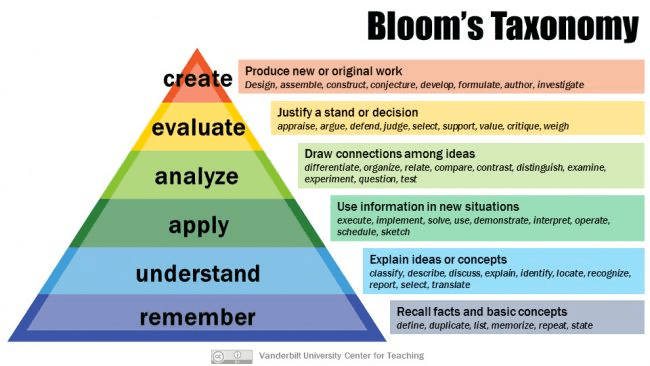

Slavin (1989) communicates that for collaborative learning to be effective, group goals must be established in addition to maintaining individual accountability. Upon reflection, I believe that within each group I could have allocated a point/question for each student to examine, ensuring all students attempted to engage in the construction of understanding. Ruggie (1998) asserts that educators must be cautious when students are involved in a group activity in order to ensure that each students’ opinions and criticism are not neglected. I believe that through implementing mixed-ability grouping and providing students the opportunity to co-construct presentations counteracted this as students practice communicating and advocating for their ideas, able to contribute to various parts of the presentation (Churchill et al., 2013). Whilst not all students were actively engaged, such learning experience provided students with the chance to ‘practice’ developing such skills prior to engaging in drama activities/games or performances throughout the unit. Within Bloom’s Taxonomy students are beckoned to shift from remembering and understanding to applying, analysing, evaluating and creating as this prompts higher order and critical thinking (Forehand, 2010). This is therefore achieved through collaboration as students are beckoned to work together, involving themselves in inquiry-based learning in order to effectively respond to the learning intention.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

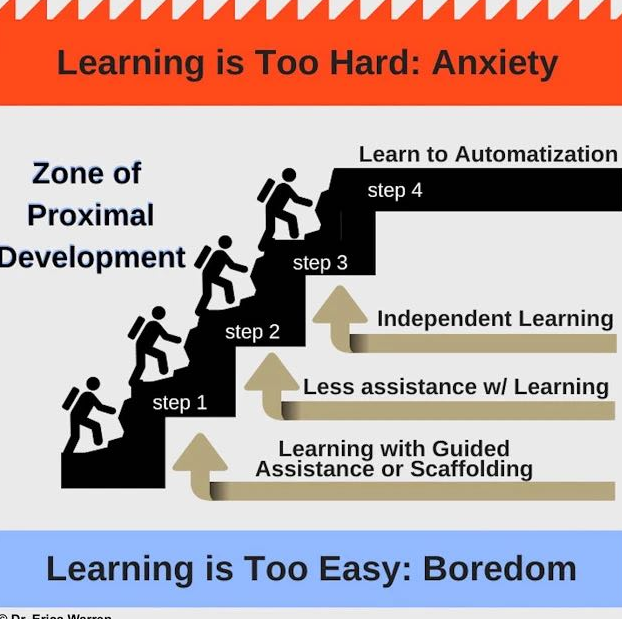

Ultimately, I believe that the collaborative learning teaching strategy I implemented helped pave the way for students to strengthen their interpersonal and intrapersonal skills. Moreover, it assisted students with recognising themselves as active learners, able to be involved in student-centred learning, prompting movement within the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). Through reflection upon the activity, I can cater collaborative learning experiences to suit each class that I may teach depending on learning levels and the need for differentiation, ultimately understanding the context of learners in my classroom and scaffolding practices accordingly (AITSL, 2017, 1.2).

Structural Learning. (n.d). Zone of Proximal Development in the Classroom. https://uploadsssl.webflow.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6184115cc19c5bf96fc45634_Conceptualising%20ZPD.jpg

REFERENCES

- Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2017). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/standards

- Churchill, S., Godinho, S., Johnson, N. F.; Keddie, A., Letts, W.; Lowe, K.; Mackay, J.; McGill, M.; Moss, J.; Nagel, M.; Shaw, K.; Vick, M. (2013). Teaching: Making a difference (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Forehand, M. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology, 41(4), 47-56. https://www.d41.org/cms/lib/IL01904672/Centricity/Domain/422/BloomsTaxonomy.pdf

- Kardaleska, L. (2013). The impact of Jigsaw approach on reading comprehension in the esp classroom. Journal of Teaching English for Specific and Academic Purposes, 1(1), 53-58. http://espeap.junis.ni.ac.rs/index.php/espeap/article/view/27

- Mintrop, H. (2004). Fostering constructivist communities of learners in the amalgamated multi‐discipline of social studies. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(2), 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000142500

- Ruggie, J. G. (1998). What makes the world hang together? Neo-utilitarianism and the social constructivist challenge. International Organization, 52(4), 855-885. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550770

- Sizer, TR (2004), The red pencil: Convictions from experience in education. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Slavin, R.E. (1989): Research on cooperative learning: An international perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 33: 231–243. : https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383890330401

- Structural Learning. (n.d). Zone of Proximal Development in the Classroom. https://uploadsssl.webflow.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6184115cc19c5bf96fc45634_Conceptualising%20ZPD.jpg

- Vecteezy. (2022).Teamwork, four stickmen businessmen holding connected team jigsaw puzzle pieces, hand drawn outline cartoon vector illustration.

- Victoria State Government. (2022). High Impact Teaching Strategies (HITS) https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/practice/improve/Pages/hits.aspx

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.