A. Introduction

i. a section detailing your initial identification, investigation and justification of your chosen learning space, with a focus on the particular student cohort and educational need

Anxiety is characterised by “persistent, excessive fear or worry in situations that are not threatening” (The National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). It can lead to increased fatigue (compromises the ability to be ‘present’), insomnia (impairs memory and concentration) and disengagement (socially and academically).

Psych Hub. (2019, April 17). What is Anxiety? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/BVJkf8IuRjE

Students with anxiety can often experience physical and social-emotional difficulties i.e. heart palpitations, tremors, inability to develop peer interactions. As th group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ involves students strengthening their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills through social engagement, such interactions can often exacerbate students’ feelings of anxiety. Students may appear withdrawn, unable to develop social connections and become wary of peers’ noticing their physical and emotional symptoms (Keeley & Storch, 2009, Packer & Pruitt, 2010), hindering their ability to develop the aforementioned skills. Collaborative activities are incorporated greatly within ‘junior’ rather than ‘senior’ years. Therefore, it is crucial to use this ‘space’ within this ‘transitory’ year (9) to establish ‘real world’ experiences before learning becomes increasingly self-directed.

Click here to read about a teenagers’ continuous experience with anxiety

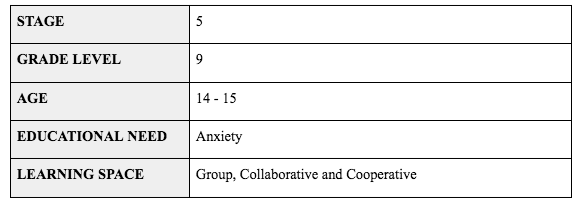

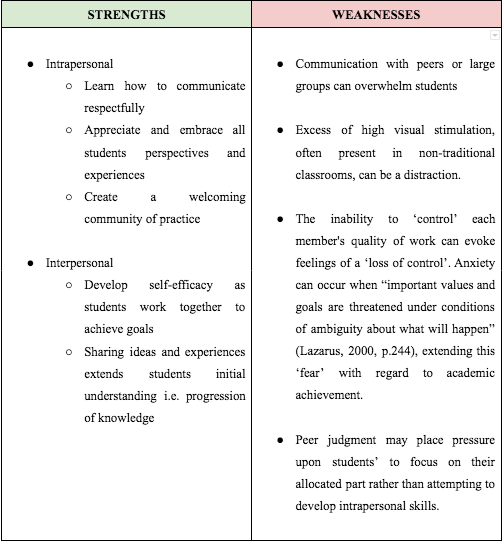

Thus, the contextual demands students are immersed within and face are ever-present and increasing. This can create an abundance of issues that exacerbate anxiety, hindering students’ ability to involve themselves in effortful group learning. Particularly, COVID-19 greatly affected students’ ability to engage in group learning. Students aged 15 to 19 revealed that education was their ‘top’ concern, followed by mental health (Mission Australia Youth Survey, 2020). Such “increased isolation and the loss of social connections” (AIHW, 2021) occurred through division from collaboration, highlighting the necessity of reflection upon this ‘space’ and the strategies implemented in order to develop students’ skills.

Click here to find out more information about the mental health of youth in Australia.

World Economic Forum. (2020). COVID-19’s staggering impact on global education

This graph shows how students’ education was greatly affected by COVID-19. As a result of closures, students were unable to partake in group learning and in particular, students with anxiety were unable to practice developing their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills within this space.

The group, collaborative and cooperative learning space, when utilised as an effective ‘tool’, can help students with anxiety recognise that there are no limitations within education.

Educators must consider the challenges they face in establishing group learning in mainstream education, catering for the needs of students with anxiety. Upon such consideration, strategies can be implemented to ensure that all students are able to thrive within independent and collaborative contexts, reaping the benefits of connecting with peers through learning

ii. A section detailing the refined description of your multimedia prototype project as a result of peer feedback received

Initial Prototype Submission

Upon consideration of peer feedback, this prototype project can be considered ‘viable’ as it aims to utilise the group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ to assist students with anxiety. Peers’ indicated that the stage level, ‘space’ and learning need linked well with each other and was considered a crucial topic to focus upon given the increase in youth anxiety.

However, it was crucial that I:

- would provide greater support, utilising literature, to indicate why this ‘space’ is important to focus upon in mainstream educational contexts.

- Consider how to ‘gently’ introduce group learning rather than instantly focus upon solution based strategies. This would help ensure the project is viable for the long term and realistic in achieving desired goals for students with anxiety.

Peers’ affirmed that there is often an abundance of weaknesses within this specific learning space. Thus, considering strategies that would help establish useful and continual practice would aid in establishing its viability. Literature provided by peers also aided in refining the prototype project to ensure that I have included implications for educators utilising this learning space, a key aspect which needed to be focused upon in order to provide optimal learning experiences for students with anxiety in this stage level.

Peer Feedback

B. A section detailing:

i. Evidencing how your prototype will enhance the learning and engagement of your chosen cohort

In Australia, 1 in 25 children and young people (13 to 17 years) experience an anxiety disorder (Queensland Government, 2022). Specifically, statistics reveal that 19% of people aged 15 to 24 struggled with anxiety between 2020 and 2021 with numbers remaining high (AIHW, 2021). This is inclusive of students within year 9, indicating the need for educators to consider its challenges and how to provide optimal learning experiences.

Nabors (2022) suggests anxiety is a ‘hidden disability’ in youth whereby the emergent behavioural issues are attributed to stereotypical ‘teenage’ angst. However, educators can “create the collective capacity for initiating and sustaining ongoing improvement in their professional practice so each student they serve can receive the highest quality of education possible” (Pugach & Johnson, 2002, p.6). Thus, it is crucial to ‘sustain’ continuous change, addressing all student ‘needs’, through understanding that anxiety is prevalent in youth within the twenty-first century given the plethora of issues they face internally and externally i.e. high levels of anxiety stemming from COVID-19 (Hawes et al., 2021).

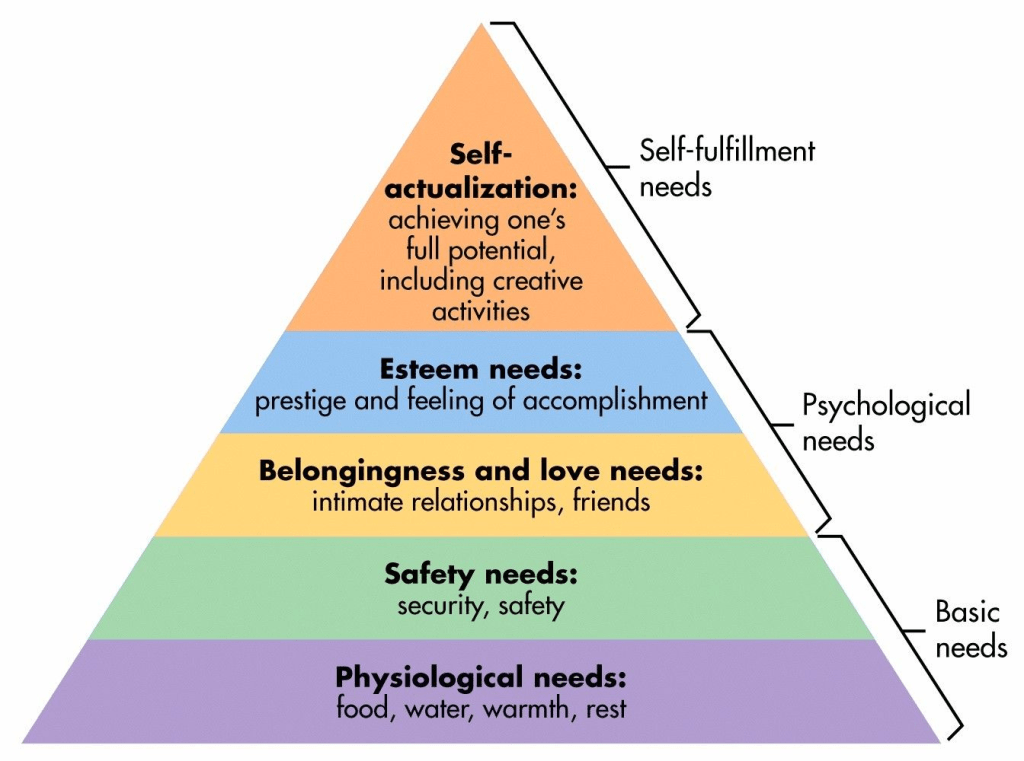

Simple Psychology. (2022). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Whilst shifting from ‘autonomy’ to ‘community’ can often exacerbate anxiety, collaborative spaces are viewed as an increasingly popular mode of human engagement (Leonard & Leonard, 2001). Stahl & Hakkarainen (2021) assert that collaboration is a “source of cognitive development…considered a basis of all human learning, not just an optional and rare mode of instruction…is a foundation of human cognition (planning, problem solving, deduction, storytelling etc) at all levels” (p. 27). It is crucial to avoid adopting an ‘avoidance’ mindset with regard to students undertaking learning in collaborative contexts as this would not prepare students for ‘real world’ practices in an evolving society (Ghandour et al., 2019).

According to Pantiz (1999), the group, collaborative and cooperative learning space can help students:

- develop social support

- diversity understanding

- establish a positive atmosphere for modelling and developing learning communities (learn from peers).

- increase self-esteem through student-centred instruction.

- develop meaningful rapports between peers and the educator

- develop critical thinking skills and conflict resolution.

Given that within Year 9 students are in the process of developing their cognitive and social skills, it is crucial to utilise this space in order to achieve this rather than relying on teacher-oriented instruction.

Vecteezy. (2022).Teamwork, four stickmen businessmen holding connected team jigsaw puzzle pieces, hand drawn outline cartoon vector illustration.

ii. Potential challenges for educators implementing your prototype learning space

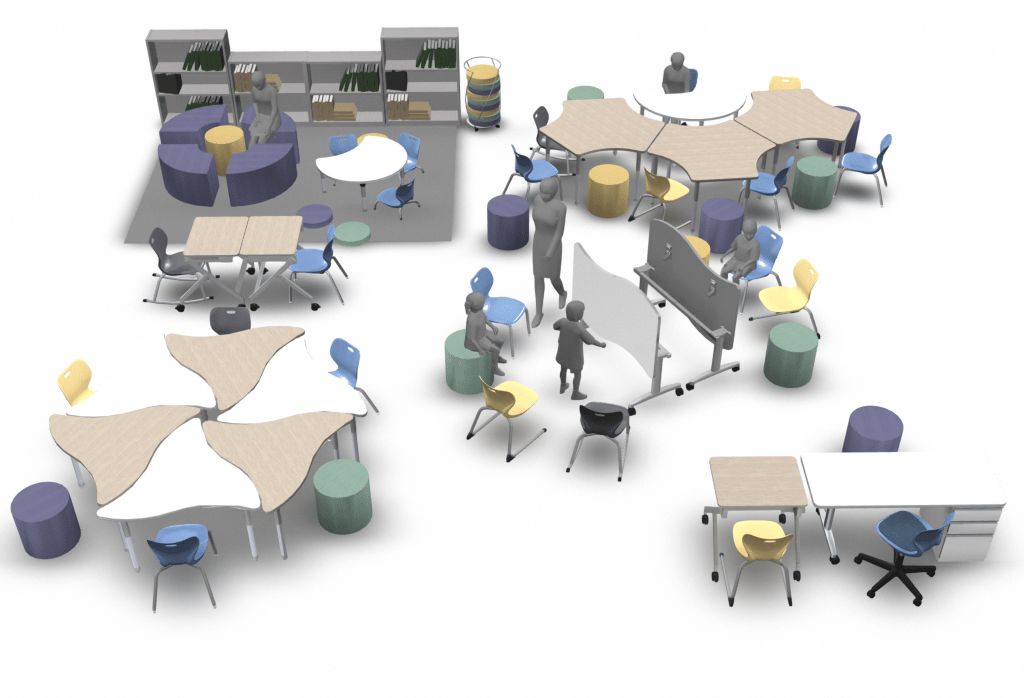

Whilst the group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ provides many benefits for students with anxiety, it can be challenging for educators to provide optimal learning experiences. This learning ‘space’ is increasingly student-directed. As the educator acts as an ‘assistor’, promoting greater student agency, it can be difficult for educators to continuously monitor all students’ activity and provide tailored care in non-traditional environments (England et al., 2017). Nilsson (2016) asserts that “the design of the collaborative classroom emphasises group learning” (p.3), mirrored through round tables, ‘break out’ spaces and open spaces to encourage movement. It can thus be difficult in such a context to continuously monitor all students’ progression.

Springer. (2020). How a collaborative classroom enables deeper learning.

Educators may face challenges assigning groups that would ensure all students are productive and within a suitable environment i.e same or mixed ability and keep track of each students’ academic achievement. Additionally, time management pressures in conjunction with fulfilling curriculum expectations can be difficult in sustaining long term goals for students with anxiety (Redes, 2016). Educators may not be equipped with the skills to consider how to utilise the group learning space as an effective tool for students with anxiety. According to Alvarez (2010), the lack of experience, knowledge and training can often lead to disorganised planning, lack of commitment to scaffolding tasks and inability to experience a desired ‘social presence’ in the classroom. An additional challenge is that continuous professional development or evolution in teaching practice can make it difficult to ‘keep up to date’ with effective strategies to implement (Bikowski, 2015).

Educators’ must consider the various challenges and how they influence students’ ability to connect themselves to real world experiences. Without educator awareness of anxiety within the collaborative space, it can be difficult to sustain ongoing, effective change.

iii. Potential challenges for your chosen student cohort whilst working within your prototype learning space

Whilst working within the group, collaborative and cooperative learning space, students with anxiety can face numerous challenges.

Given that Year 9 are a ‘junior’ cohort, still in the process of developing necessary academic, social and cognitive skills, it is crucial to provide explicit instruction to guide behaviour and achievement (Hänze & Berger, 2007). This ‘space’ has been established as largely student-directed and thus such lack of direction, scaffolding and teacher inclusion can often increase students’ anxiety. Collaboration without stating explicit learning objectives may create a ‘disjointed’ learning ethic, contribute to unequal activities and overwhelm students’ metacognition (Liu et al., 2010). Furthermore, students may feel a lack of control over group members’ involvement and responsibilities over assigned tasks, leading to altered participating experiences and anxiety over performance (Hall & Buzwell, 2013, Lazarus, 2000).

Peer judgment may also place pressure upon students’ to focus on their allocated ‘group work’ section rather than strengthening interpersonal skills.

Planet Neurodivergent. (2021). Social Anxiety. https://i0.wp.com/www.planetneurodivergent.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/social-anxiety-disorder.jpg?fit=900%2C600&ssl=1

Within this ‘space’, students are beckoned to develop collaborative skills concurrently with their academic and discipline skills. It can often be difficult and overwhelming to manage these simultaneously and creates increased pressure upon students with anxiety (Moran, 2016). Moreover, an overwhelming amount of high visual stimuli i.e. bright colours, present within collaborative rather than ‘traditional’ learning spaces, can make students with anxiety uncomfortable, affecting their ability to be ‘present’ (Moran, 2016).

iv. Recommendations for approaches to resolving the challenges identified in (ii) and (iii)

Educators’ and peers can establish a welcoming ‘community of practice’ within the group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ in order to assist in resolving challenges that students with anxiety face within this context. Whilst it is crucial to minimise provoking anxiety within such contexts, it is unlikely that this is avoided entirely. It is therefore important to help students build skills to regulate their emotions within this learning ‘space’.

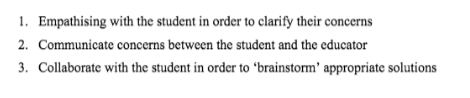

Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) enables students with anxiety to build such skills by practicing problem solving and conflict resolution with peers and educators (Ablon & Pollastri, 2018). It is important for educators to monitor students in order to recognise ‘triggers’ and develop a rapport with them in order to help address them within this ‘space’. Three key steps to take include:

Check out this video on a new, Australian school program actively teaching kids how to recognise and deal with anxiety:

ABC News. (2022, March 14). New school program teaching kids how to recognise and deal with anxiety. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2te2FcFwyQQ

‘Group’ reassurance can be beneficial in minimising anxiety during collaboration, however, it is not a direct long term strategy to ‘change’ inaccurate thinking (Minahan, 2014). Verbalising thoughts and feelings can strengthen a rapport and increase students’ with anxieties’ sense of belonging within the group learning context (Coplan & Weeks, 2009).

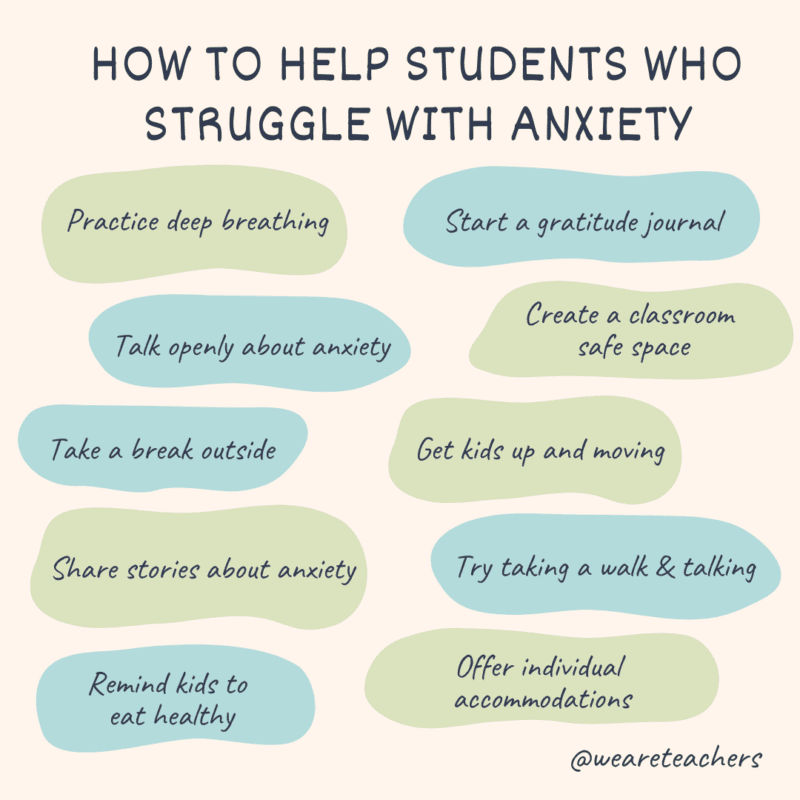

The educator can Provide breaks for students to self-regulate i.e. walk, listen to relaxing music and practice meditation (Gasparovich, 2008)

Encouraging self-reflection i.e. journaling and feedback and providing meetings with educators can help ascertain the effectiveness of strategies implemented and possible adjustments to cater for students with anxiety’s needs and maintain their involvement.

Students with anxiety, in collaborative contexts, thrive when provided with a consistent schedule and clear expectations. Before undertaking group learning, provide the student with an updated routine in advance and reach out to clarify that there will be a change in environment (Zentall, 2005).

Providing students with anxiety a ‘pass’ during group activities may allow them to leave the environment when they are becoming increasingly overwhelmed. Packer & Pruitt (2010) assert that “the ability to make a graceful exit is important to the student’s self-esteem and peer relationships” (p.45). Provision of such ‘breaks’ can enable students to feel safe, supported, work at a comfortable pace and feel encouraged to ‘re-enter’ when they feel able to.

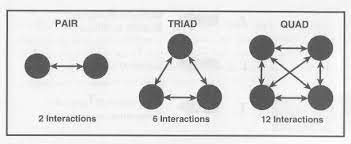

Allocating a smaller group size can be beneficial in establishing collaborative practices for students with anxiety (Dishon & O’Leary, 1998). Pre-allocating group roles can help structure groups according to ability and control group size so as to not exacerbate students’ with anxiety’s fear of working with too many peers. Thus, beginning with pairs or triads may be helpful in gradually instilling in students the capacity to work in group environments (Scager et al., 2016).

Primary Professional Development Service. What is the ideal group size? https://www.pdst.ie/sites/default/files/Session%203%20-%20PS%20Co%20-%20Op%20%EF%80%A2%20Group%20Work.pdf

Educators can avoid hovering over students with anxiety as they work within groups in order to not provoke them feeling overwhelmed and intimidated. Instead, educators can make themselves readily available in the classroom and shift their presence evenly to maintain support (Plotinsky, 2022).

Remind students that being critiqued and evaluated by peers can be a positive experience and is constantly occurring in ‘real world’ experiences. In order to continually reinforce this, inviting students to provide peer feedback during lesson activities. This can occur through anonymous polls or ‘padlet comments’ of which can help restructure students’ mindsets and contribute to greater involvement in the group, collaborative and cooperative environment (Pollock, 2016).

Implementation of technology and interactive features rather than pure ‘face to face’ group work can help gradually shift from autonomy to cooperation (Han et al., 2014). This may take the form of collaborative google docs or slideshow presentations.

Check out this video on how technology can be used to GRADUALLY ease students with anxiety into collaborative learning.

Katherine Hixon. (2020, April 30). Using Technology to Support Collaborative Learning. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PRbhT3Xdq5w

Click here to read more about ‘How a Collaborative Classroom enables deeper learning’ and click here to read about more strategies for teachers.

C. Concluding comments

Anxiety is regarded as a prevalent mental health condition affecting the Australian youth population. Avoidance of the group, collaborative and cooperative learning space is unlikely to assist students in developing their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills. This learning ‘space’ helps strengthen students’ confidence in themselves and interaction with peers, enabling them to deepen their sense of understanding and relationships (Packer & Pruitt, 2010). Thus, it must be utilised effectively by the educator and peers in order to consider the challenges both parties face and implement appropriate long term solutions (Barkley et. al, 2014).