My journey to become a high school educator has been an insightful one, inviting me to appreciate that the education profession is complex and constantly evolving. I am approaching my final placement as part of the Bachelor of Teaching/ Bachelor of Arts (Humanities) degree at Australian Catholic University, specialising in History and English. Throughout the completion of previous professional experience opportunities, I gained and developed valuable skills. I taught at an all-girls public high school as well as a co-educational catholic high school whereby I immersed myself within each respective community, embracing their values and upholding their policies. These experiences catalysed profound changes whereby I began to understand myself as an educator, recognise that human experiences are diverse and appreciate that I have the opportunity to facilitate meaningful learning experiences. Teaching is entrenched within many aspects of my life. I have obtained my conditional accreditation to work as a casual educator, offer tutoring services and I am a volunteer Sunday School teacher for primary aged children. These experiences have strengthened my ability to build a strong rapport with students’, scaffold/deliver a wide range of lessons, differentiate learning and can consider myself as a reflective educator.

REFERENCES

Ablon, J. S., & Pollastri, A. R. (2018). The school discipline fix: changing behavior using the collaborative problem solving approach. WW Norton & Company.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021, June 25). COVID-19 and the impact on young people. AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/covid-19-and-young-people

Barkley, E.F., Major, C.H., & Cross, K.P. (2014). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A handbook for college faculty (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass

Bikowski, D. (2015). The Pedagogy of Collaboration: teaching effectively within an evolving technology landscape. Innovation in English language teacher education, 223-231.

Dishon, D., & O‘Leary, P.W. (1998). Guidebook for cooperative learning: Techniques for creating more effective schools (3rd ed.). Learning Publications.

England, B. J., Brigati, J. R., & Schussler, E. E. (2017). Student anxiety in introductory biology classrooms: Perceptions about active learning and persistence in the major. PloS one, 12(8), e0182506.

Gasparovich, L. (2008). Positive behavior support: Learning to prevent or manage anxiety in the school setting (Newsletter). Retrieved from www.sbbh.pitt.edu/files/other/Anxiety_LNG_newsletter.pdf

Ghandour, R. M., Sherman, L. J., Vladutiu, C. J., Ali, M. M., Lynch, S. E., Bitsko, R. H., & Blumberg, S. J. (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. The Journal of pediatrics, 206, 256-267.

Hall, D., & Buzwell, S. (2013). The problem of free-riding in group projects: Looking beyond social loafing as reason for non-contribution. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14(1), 37-49.

Han, A.N., Leong, L. C., & Nair, K.P. (2014). X-Space Model: Taylor’s University’s Collaborative Classroom Design and Process. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 123, 272–279.

Hänze, M., & Berger, R. (2007). Cooperative learning, motivational effects, and student characteristics: An experimental study comparing cooperative learning and direct instruction in 12th grade physics classes. Learning and instruction, 17(1), 29-41.

Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G., & Nelson, B. D. (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1-9.

Keeley, M. L., & Storch, E. A. (2009). Anxiety disorders in youth. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24(1), 26–40.

Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Toward better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55(6), 665–673. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.665

Leonard, P. E., & Leonard, L.J. (2001). The collaborative prescription: Remedy or reverie? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 4(4); pp. 383–99.

Liu, S., Joy, M., & Griffiths, N. (2010, July). Students’ perceptions of the factors leading to unsuccessful group collaboration. In 2010 10th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 565-569). IEEE.

Minahan, J. (2014). The behavior code companion: Strategies, tools, and interventions for supporting students with anxiety-related or oppositional behaviors. Harvard Education Press.

Mission Australia. (2020). Youth Survey Report 2020. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth-survey/1719-mission-australia-youth-survey-infographic-2020/file

Moran, K. (2016). Anxiety in the classroom: Implications for middle school teachers. Middle School Journal, 47(1), 27-32.

Nabors L. (2022). Conduct problems and anxiety in children. In Anxiety management in children with mental and physical health problems (pp. 117–133). Springer.

Nilsson, B. (2016, January 11). What’s a Collaborative Classroom and Why is It Important? Extreme. https://www.extremenetworks.com/extreme-networks-blog/ whats-a-collaborative-classroom-and-why-is-it-important/

Packer, L. E., & Pruitt, S. K. (2010). Challenging kids, challenged teachers: Teaching students with Tourette’s, Bipolar disorders, Executive dysfunction, OCD, ADHD, and more. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

Panitz, T. (1999). The motivational benefits of cooperative learning. New directions for teaching and learning, 78, 59-67.

Plotinsky, M. (2022). Teach More, Hover Less: How to Stop Micromanaging Your Secondary Classroom. WW Norton & Company.

Pollock, M. (2016). Smart Tech Use for Equity. The Education Digest, 81, 40-45. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1768622785?accountid=14723

Pugach, M.C., & Johnson, L.J. (2002). Collaborative Practitioners, Collaborative Schools. 2nd ed. Denver: Love Publishing.

Queensland Government. 2022. https://www.qld.gov.au/youth/looking-after-your-mental-health/managing-your-thoughts/anxiety.

Redes, A. (2016). Collaborative learning and teaching in practice. Journal Plus Education, 16(2), 334-345.

Alvarez, CGS. (2010). Considerations in the implementation of collaborative learning in the classroom with the support of information and communication technology. INTEREDU Magazine, 2 (2), 43-52.

Scager, K., Boonstra, J., Peeters, T., Vulperhorst, J., & Wiegant, F. (2016). Collaborative learning in higher education: Evoking positive interdependence. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), ar69. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-07-0219

Stahl, G., & Hakkarainen, K. (2021). Theories of CSCL. In International handbook of computer-supported collaborative learning (pp. 23-43). Springer, Cham.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2017). Anxiety Disorders. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders

Weeks, M., Coplan, R. J., & Kingsbury, A. (2009). The correlates and consequences of early appearing social anxiety in young children. Journal of anxiety disorders, 23(7), 965-972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.06.006

Zentall, S. S. (2005). Theory‐and evidence‐based strategies for children with attentional problems. Psychology in the Schools, 42(8), 821-836. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20114

ANXIETY IN THE ‘GROUP, COLLABORATIVE AND COOPERATIVE’ LEARNING SPACE

A. Introduction

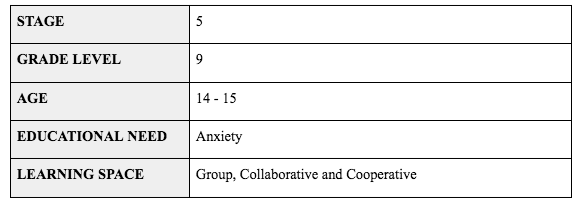

i. a section detailing your initial identification, investigation and justification of your chosen learning space, with a focus on the particular student cohort and educational need

Anxiety is characterised by “persistent, excessive fear or worry in situations that are not threatening” (The National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). It can lead to increased fatigue (compromises the ability to be ‘present’), insomnia (impairs memory and concentration) and disengagement (socially and academically).

Psych Hub. (2019, April 17). What is Anxiety? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/BVJkf8IuRjE

Students with anxiety can often experience physical and social-emotional difficulties i.e. heart palpitations, tremors, inability to develop peer interactions. As th group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ involves students strengthening their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills through social engagement, such interactions can often exacerbate students’ feelings of anxiety. Students may appear withdrawn, unable to develop social connections and become wary of peers’ noticing their physical and emotional symptoms (Keeley & Storch, 2009, Packer & Pruitt, 2010), hindering their ability to develop the aforementioned skills. Collaborative activities are incorporated greatly within ‘junior’ rather than ‘senior’ years. Therefore, it is crucial to use this ‘space’ within this ‘transitory’ year (9) to establish ‘real world’ experiences before learning becomes increasingly self-directed.

Click here to read about a teenagers’ continuous experience with anxiety

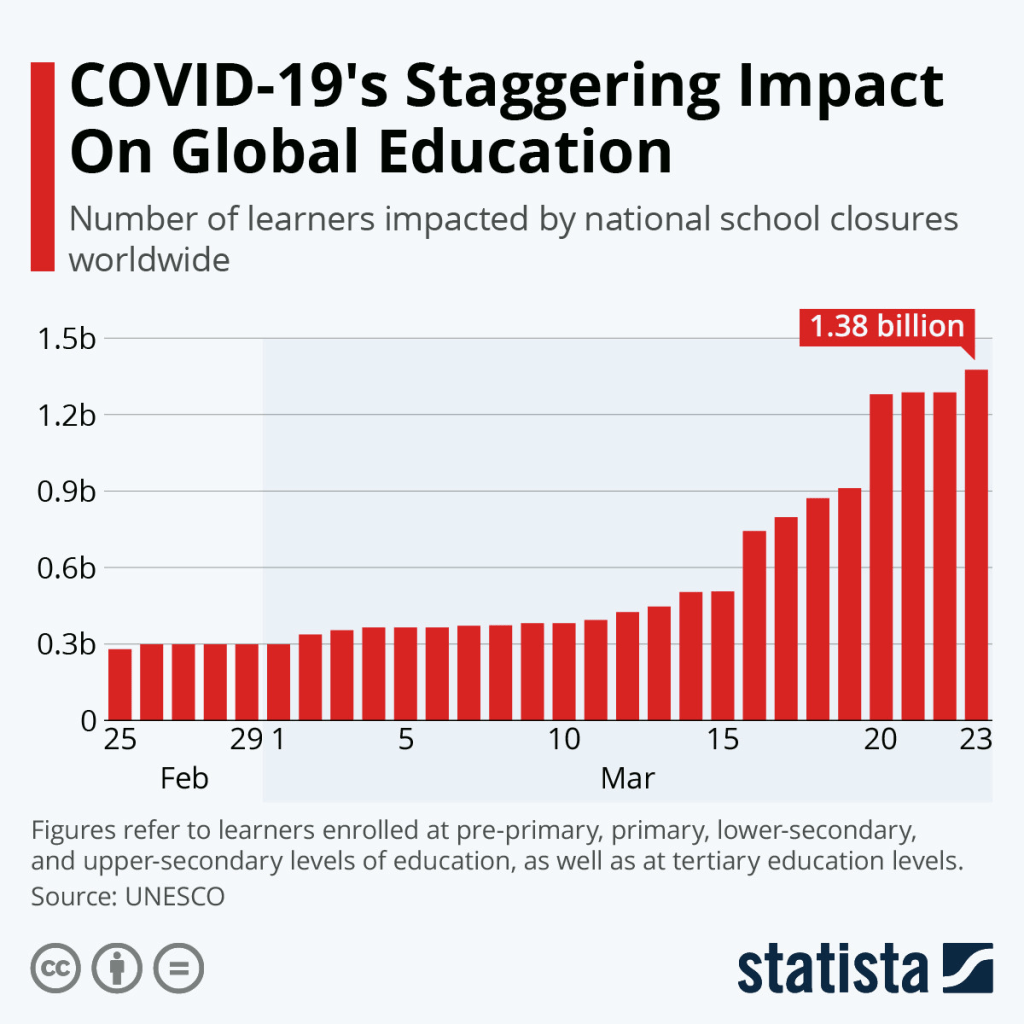

Thus, the contextual demands students are immersed within and face are ever-present and increasing. This can create an abundance of issues that exacerbate anxiety, hindering students’ ability to involve themselves in effortful group learning. Particularly, COVID-19 greatly affected students’ ability to engage in group learning. Students aged 15 to 19 revealed that education was their ‘top’ concern, followed by mental health (Mission Australia Youth Survey, 2020). Such “increased isolation and the loss of social connections” (AIHW, 2021) occurred through division from collaboration, highlighting the necessity of reflection upon this ‘space’ and the strategies implemented in order to develop students’ skills.

Click here to find out more information about the mental health of youth in Australia.

World Economic Forum. (2020). COVID-19’s staggering impact on global education

This graph shows how students’ education was greatly affected by COVID-19. As a result of closures, students were unable to partake in group learning and in particular, students with anxiety were unable to practice developing their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills within this space.

The group, collaborative and cooperative learning space, when utilised as an effective ‘tool’, can help students with anxiety recognise that there are no limitations within education.

Educators must consider the challenges they face in establishing group learning in mainstream education, catering for the needs of students with anxiety. Upon such consideration, strategies can be implemented to ensure that all students are able to thrive within independent and collaborative contexts, reaping the benefits of connecting with peers through learning

ii. A section detailing the refined description of your multimedia prototype project as a result of peer feedback received

Initial Prototype Submission

Upon consideration of peer feedback, this prototype project can be considered ‘viable’ as it aims to utilise the group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ to assist students with anxiety. Peers’ indicated that the stage level, ‘space’ and learning need linked well with each other and was considered a crucial topic to focus upon given the increase in youth anxiety.

However, it was crucial that I:

- would provide greater support, utilising literature, to indicate why this ‘space’ is important to focus upon in mainstream educational contexts.

- Consider how to ‘gently’ introduce group learning rather than instantly focus upon solution based strategies. This would help ensure the project is viable for the long term and realistic in achieving desired goals for students with anxiety.

Peers’ affirmed that there is often an abundance of weaknesses within this specific learning space. Thus, considering strategies that would help establish useful and continual practice would aid in establishing its viability. Literature provided by peers also aided in refining the prototype project to ensure that I have included implications for educators utilising this learning space, a key aspect which needed to be focused upon in order to provide optimal learning experiences for students with anxiety in this stage level.

Peer Feedback

B. A section detailing:

i. Evidencing how your prototype will enhance the learning and engagement of your chosen cohort

In Australia, 1 in 25 children and young people (13 to 17 years) experience an anxiety disorder (Queensland Government, 2022). Specifically, statistics reveal that 19% of people aged 15 to 24 struggled with anxiety between 2020 and 2021 with numbers remaining high (AIHW, 2021). This is inclusive of students within year 9, indicating the need for educators to consider its challenges and how to provide optimal learning experiences.

Nabors (2022) suggests anxiety is a ‘hidden disability’ in youth whereby the emergent behavioural issues are attributed to stereotypical ‘teenage’ angst. However, educators can “create the collective capacity for initiating and sustaining ongoing improvement in their professional practice so each student they serve can receive the highest quality of education possible” (Pugach & Johnson, 2002, p.6). Thus, it is crucial to ‘sustain’ continuous change, addressing all student ‘needs’, through understanding that anxiety is prevalent in youth within the twenty-first century given the plethora of issues they face internally and externally i.e. high levels of anxiety stemming from COVID-19 (Hawes et al., 2021).

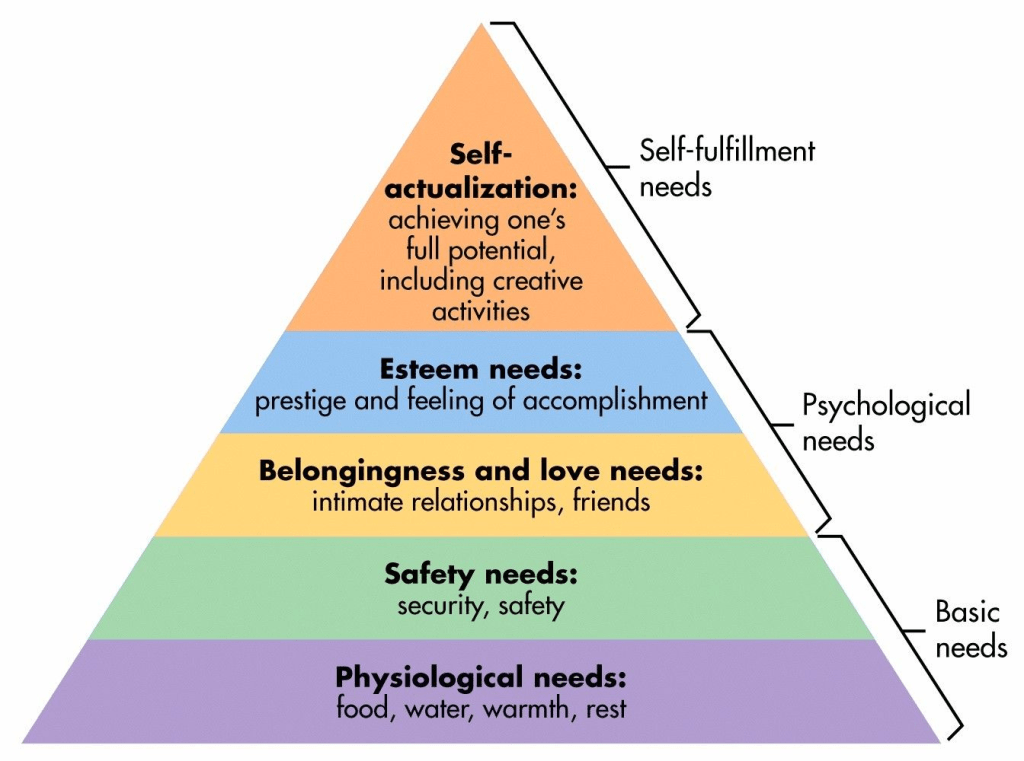

Simple Psychology. (2022). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Whilst shifting from ‘autonomy’ to ‘community’ can often exacerbate anxiety, collaborative spaces are viewed as an increasingly popular mode of human engagement (Leonard & Leonard, 2001). Stahl & Hakkarainen (2021) assert that collaboration is a “source of cognitive development…considered a basis of all human learning, not just an optional and rare mode of instruction…is a foundation of human cognition (planning, problem solving, deduction, storytelling etc) at all levels” (p. 27). It is crucial to avoid adopting an ‘avoidance’ mindset with regard to students undertaking learning in collaborative contexts as this would not prepare students for ‘real world’ practices in an evolving society (Ghandour et al., 2019).

According to Pantiz (1999), the group, collaborative and cooperative learning space can help students:

- develop social support

- diversity understanding

- establish a positive atmosphere for modelling and developing learning communities (learn from peers).

- increase self-esteem through student-centred instruction.

- develop meaningful rapports between peers and the educator

- develop critical thinking skills and conflict resolution.

Given that within Year 9 students are in the process of developing their cognitive and social skills, it is crucial to utilise this space in order to achieve this rather than relying on teacher-oriented instruction.

Vecteezy. (2022).Teamwork, four stickmen businessmen holding connected team jigsaw puzzle pieces, hand drawn outline cartoon vector illustration.

ii. Potential challenges for educators implementing your prototype learning space

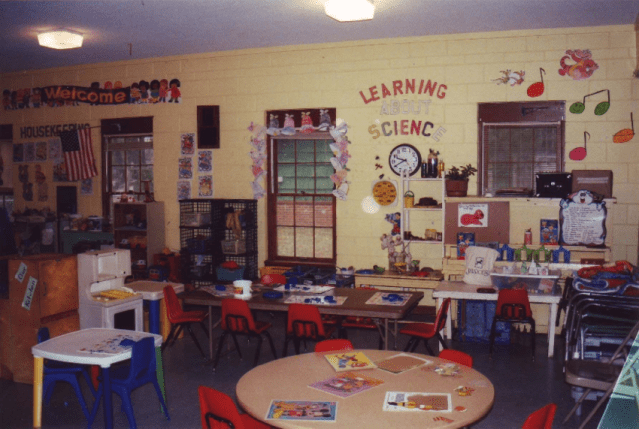

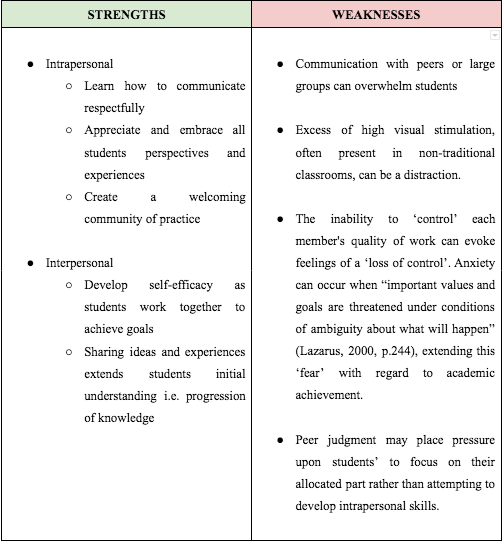

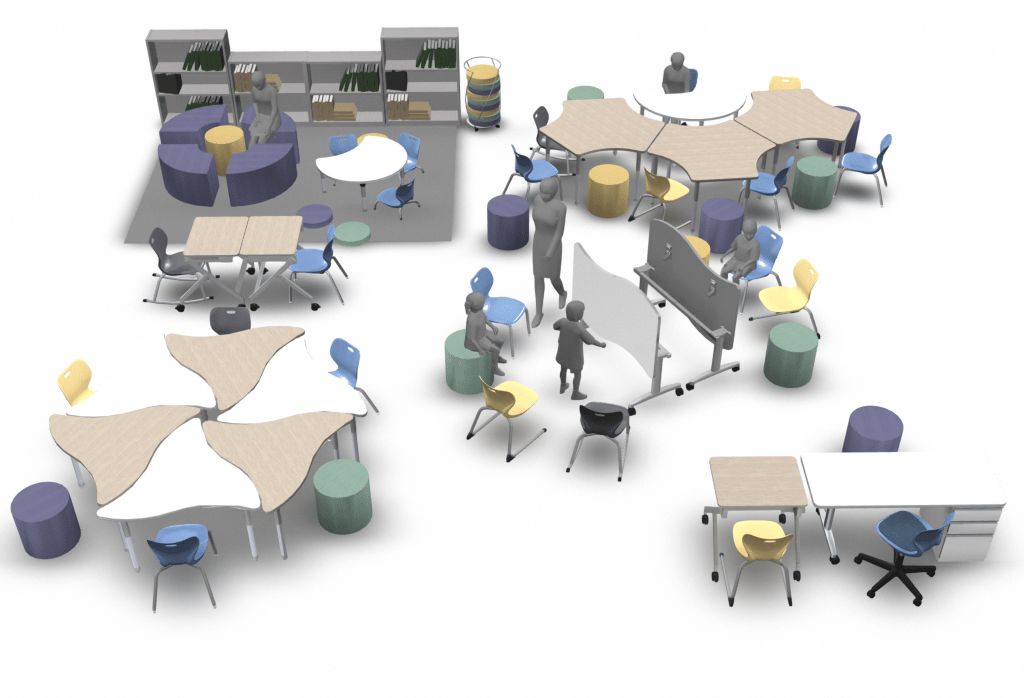

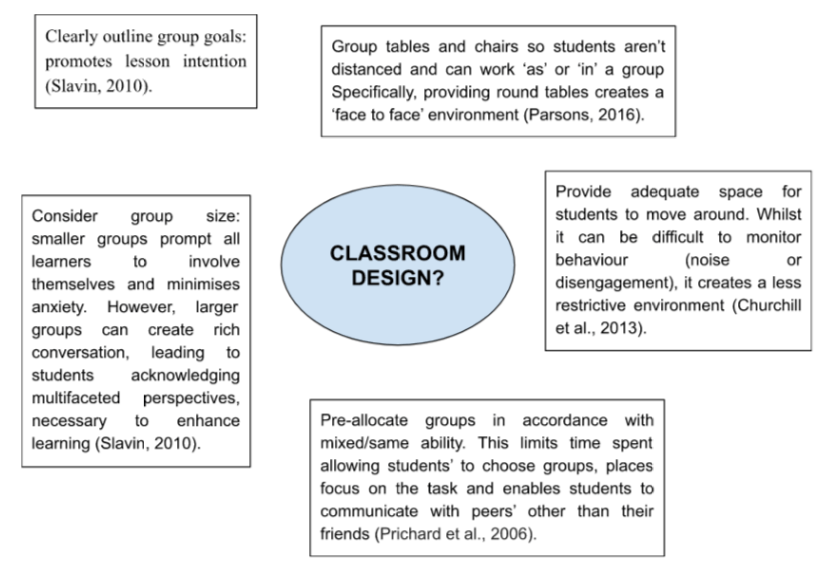

Whilst the group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ provides many benefits for students with anxiety, it can be challenging for educators to provide optimal learning experiences. This learning ‘space’ is increasingly student-directed. As the educator acts as an ‘assistor’, promoting greater student agency, it can be difficult for educators to continuously monitor all students’ activity and provide tailored care in non-traditional environments (England et al., 2017). Nilsson (2016) asserts that “the design of the collaborative classroom emphasises group learning” (p.3), mirrored through round tables, ‘break out’ spaces and open spaces to encourage movement. It can thus be difficult in such a context to continuously monitor all students’ progression.

Springer. (2020). How a collaborative classroom enables deeper learning.

Educators may face challenges assigning groups that would ensure all students are productive and within a suitable environment i.e same or mixed ability and keep track of each students’ academic achievement. Additionally, time management pressures in conjunction with fulfilling curriculum expectations can be difficult in sustaining long term goals for students with anxiety (Redes, 2016). Educators may not be equipped with the skills to consider how to utilise the group learning space as an effective tool for students with anxiety. According to Alvarez (2010), the lack of experience, knowledge and training can often lead to disorganised planning, lack of commitment to scaffolding tasks and inability to experience a desired ‘social presence’ in the classroom. An additional challenge is that continuous professional development or evolution in teaching practice can make it difficult to ‘keep up to date’ with effective strategies to implement (Bikowski, 2015).

Educators’ must consider the various challenges and how they influence students’ ability to connect themselves to real world experiences. Without educator awareness of anxiety within the collaborative space, it can be difficult to sustain ongoing, effective change.

iii. Potential challenges for your chosen student cohort whilst working within your prototype learning space

Whilst working within the group, collaborative and cooperative learning space, students with anxiety can face numerous challenges.

Given that Year 9 are a ‘junior’ cohort, still in the process of developing necessary academic, social and cognitive skills, it is crucial to provide explicit instruction to guide behaviour and achievement (Hänze & Berger, 2007). This ‘space’ has been established as largely student-directed and thus such lack of direction, scaffolding and teacher inclusion can often increase students’ anxiety. Collaboration without stating explicit learning objectives may create a ‘disjointed’ learning ethic, contribute to unequal activities and overwhelm students’ metacognition (Liu et al., 2010). Furthermore, students may feel a lack of control over group members’ involvement and responsibilities over assigned tasks, leading to altered participating experiences and anxiety over performance (Hall & Buzwell, 2013, Lazarus, 2000).

Peer judgment may also place pressure upon students’ to focus on their allocated ‘group work’ section rather than strengthening interpersonal skills.

Planet Neurodivergent. (2021). Social Anxiety. https://i0.wp.com/www.planetneurodivergent.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/social-anxiety-disorder.jpg?fit=900%2C600&ssl=1

Within this ‘space’, students are beckoned to develop collaborative skills concurrently with their academic and discipline skills. It can often be difficult and overwhelming to manage these simultaneously and creates increased pressure upon students with anxiety (Moran, 2016). Moreover, an overwhelming amount of high visual stimuli i.e. bright colours, present within collaborative rather than ‘traditional’ learning spaces, can make students with anxiety uncomfortable, affecting their ability to be ‘present’ (Moran, 2016).

iv. Recommendations for approaches to resolving the challenges identified in (ii) and (iii)

Educators’ and peers can establish a welcoming ‘community of practice’ within the group, collaborative and cooperative learning ‘space’ in order to assist in resolving challenges that students with anxiety face within this context. Whilst it is crucial to minimise provoking anxiety within such contexts, it is unlikely that this is avoided entirely. It is therefore important to help students build skills to regulate their emotions within this learning ‘space’.

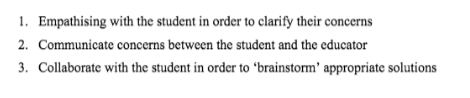

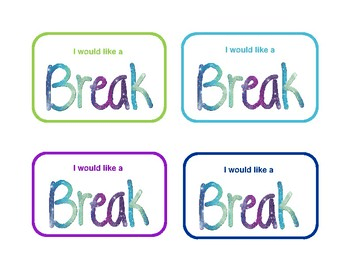

Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) enables students with anxiety to build such skills by practicing problem solving and conflict resolution with peers and educators (Ablon & Pollastri, 2018). It is important for educators to monitor students in order to recognise ‘triggers’ and develop a rapport with them in order to help address them within this ‘space’. Three key steps to take include:

Check out this video on a new, Australian school program actively teaching kids how to recognise and deal with anxiety:

ABC News. (2022, March 14). New school program teaching kids how to recognise and deal with anxiety. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2te2FcFwyQQ

‘Group’ reassurance can be beneficial in minimising anxiety during collaboration, however, it is not a direct long term strategy to ‘change’ inaccurate thinking (Minahan, 2014). Verbalising thoughts and feelings can strengthen a rapport and increase students’ with anxieties’ sense of belonging within the group learning context (Coplan & Weeks, 2009).

The educator can Provide breaks for students to self-regulate i.e. walk, listen to relaxing music and practice meditation (Gasparovich, 2008)

Encouraging self-reflection i.e. journaling and feedback and providing meetings with educators can help ascertain the effectiveness of strategies implemented and possible adjustments to cater for students with anxiety’s needs and maintain their involvement.

Students with anxiety, in collaborative contexts, thrive when provided with a consistent schedule and clear expectations. Before undertaking group learning, provide the student with an updated routine in advance and reach out to clarify that there will be a change in environment (Zentall, 2005).

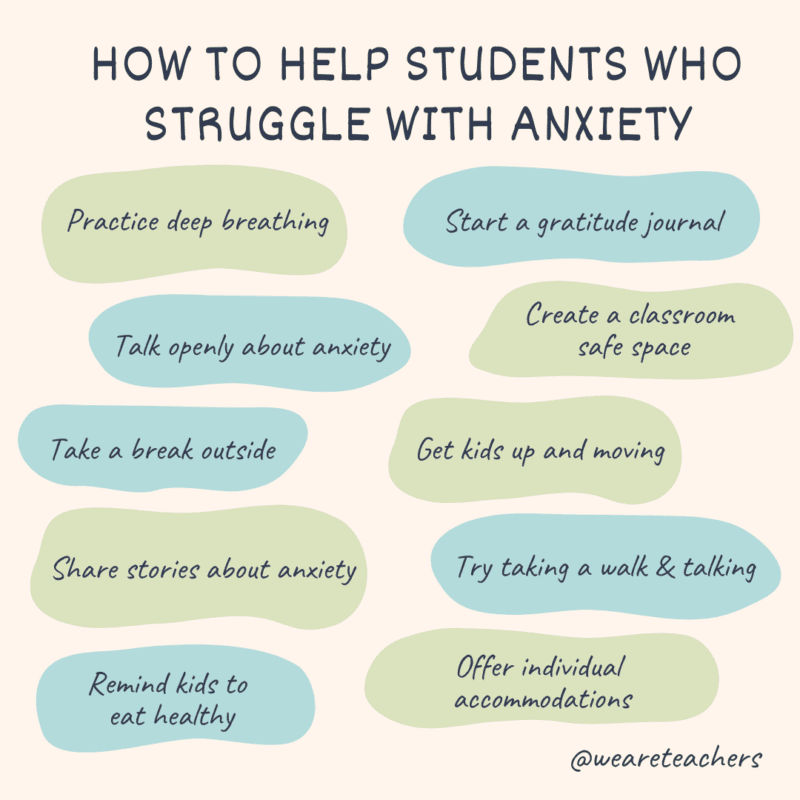

Providing students with anxiety a ‘pass’ during group activities may allow them to leave the environment when they are becoming increasingly overwhelmed. Packer & Pruitt (2010) assert that “the ability to make a graceful exit is important to the student’s self-esteem and peer relationships” (p.45). Provision of such ‘breaks’ can enable students to feel safe, supported, work at a comfortable pace and feel encouraged to ‘re-enter’ when they feel able to.

Allocating a smaller group size can be beneficial in establishing collaborative practices for students with anxiety (Dishon & O’Leary, 1998). Pre-allocating group roles can help structure groups according to ability and control group size so as to not exacerbate students’ with anxiety’s fear of working with too many peers. Thus, beginning with pairs or triads may be helpful in gradually instilling in students the capacity to work in group environments (Scager et al., 2016).

Primary Professional Development Service. What is the ideal group size? https://www.pdst.ie/sites/default/files/Session%203%20-%20PS%20Co%20-%20Op%20%EF%80%A2%20Group%20Work.pdf

Educators can avoid hovering over students with anxiety as they work within groups in order to not provoke them feeling overwhelmed and intimidated. Instead, educators can make themselves readily available in the classroom and shift their presence evenly to maintain support (Plotinsky, 2022).

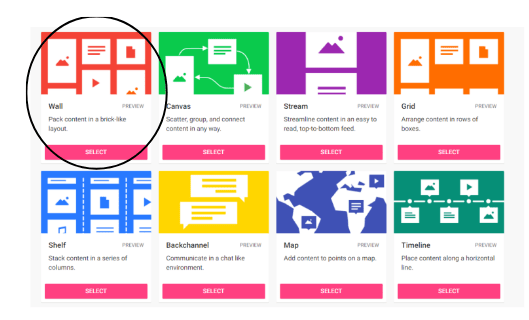

Remind students that being critiqued and evaluated by peers can be a positive experience and is constantly occurring in ‘real world’ experiences. In order to continually reinforce this, inviting students to provide peer feedback during lesson activities. This can occur through anonymous polls or ‘padlet comments’ of which can help restructure students’ mindsets and contribute to greater involvement in the group, collaborative and cooperative environment (Pollock, 2016).

Implementation of technology and interactive features rather than pure ‘face to face’ group work can help gradually shift from autonomy to cooperation (Han et al., 2014). This may take the form of collaborative google docs or slideshow presentations.

Check out this video on how technology can be used to GRADUALLY ease students with anxiety into collaborative learning.

Katherine Hixon. (2020, April 30). Using Technology to Support Collaborative Learning. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PRbhT3Xdq5w

Click here to read more about ‘How a Collaborative Classroom enables deeper learning’ and click here to read about more strategies for teachers.

C. Concluding comments

Anxiety is regarded as a prevalent mental health condition affecting the Australian youth population. Avoidance of the group, collaborative and cooperative learning space is unlikely to assist students in developing their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills. This learning ‘space’ helps strengthen students’ confidence in themselves and interaction with peers, enabling them to deepen their sense of understanding and relationships (Packer & Pruitt, 2010). Thus, it must be utilised effectively by the educator and peers in order to consider the challenges both parties face and implement appropriate long term solutions (Barkley et. al, 2014).

ARTICLE 7 – CRITICAL & ANALYTICAL REFLECTIONS ABOUT ONLINE LEARNING

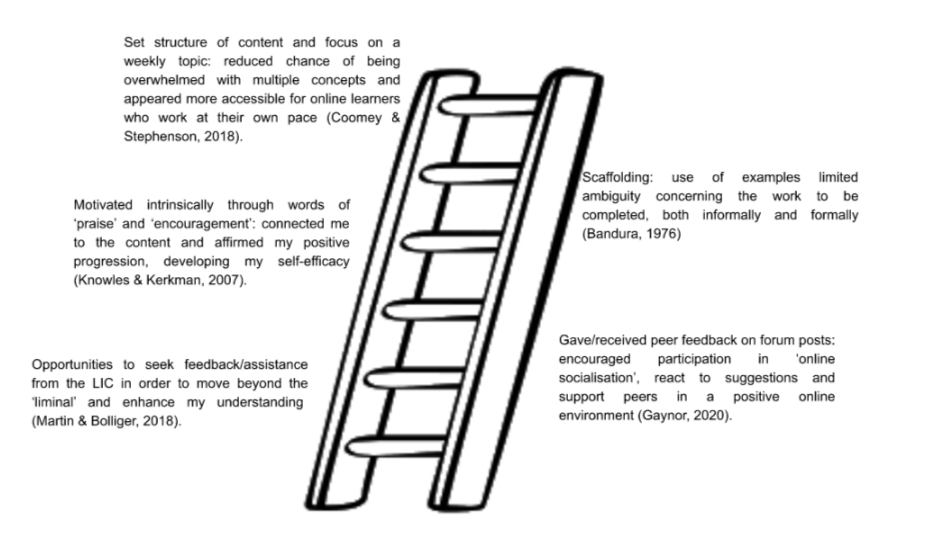

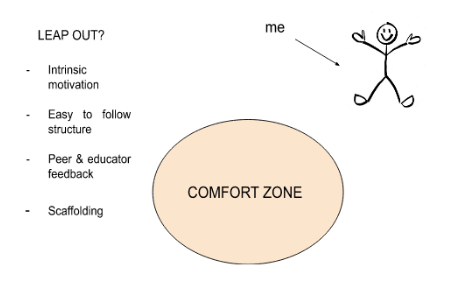

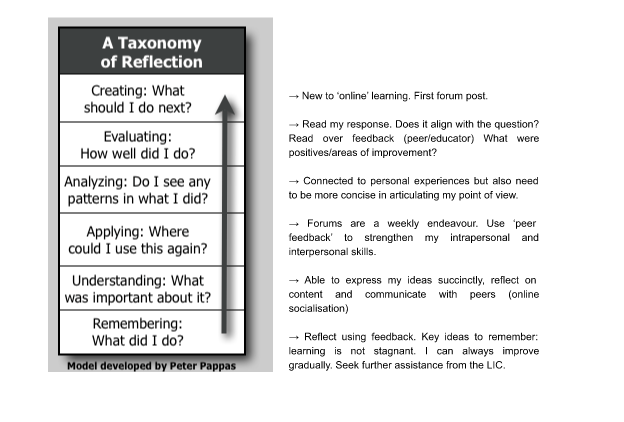

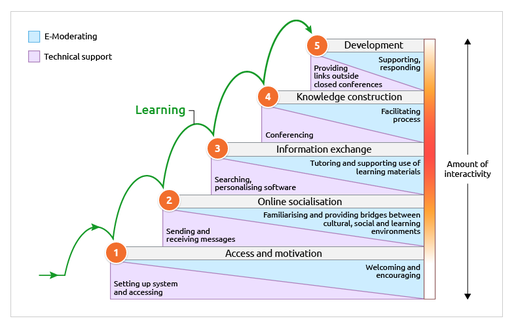

‘Learning to learn online’ has been a gradual, non-linear process. During the completion of the unit EDFD459, Learning Spaces, the educator and I have been “separated” by “time” and “distance” (Dempsey & Van Eck, 2002, p. 283), two key aspects which can influence investment in effective online learning. At first, I found myself within the ‘liminal’, uncertain about the content or tasks I would encounter and hesitant to ‘express’ myself given that the internet lives forever. However, the establishment of a supportive community of practice (Smith, 2003) enabled me to progress from Stage 1 to 2 ‘Online Socialisation’, contributing to written and verbal discussion, and now I reside in Stage 4 ‘Knowledge Construction’ (Salmon, 2011).

Link to my first post – ARTICLE 1 – LEARNING TO LEARN ONLINE

How did I progress?

I was able to ‘leap’ out of my comfort zone through the establishment of these practices. As an educator, I endeavour to consider that students require extra assistance in the online realm as there is a physical separation between the teacher and learner. Establishing a supportive CoP underpins my teaching ethos as it is the first step to encourage effortful learning.

REFERENCES

Bandura, A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review. 84 (2): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Coomey, M., & Stephenson, J. (2018). Online learning: It is all about dialogue, involvement, support and control—according to the research. In Teaching & learning online (pp. 37-52). Routledge.

Dempsey, J. V., & Van Eck, R. N. (2002). Instructional design on-line: Evolving expectations. Trends and issues in instructional design and technology, 281-294.

Gaynor, J. W. (2020). Peer review in the classroom: Student perceptions, peer feedback quality and the role of assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(5), 758-775.

Knowles, E., & Kerkman, D. (2007). An investigation of students’ attitude and motivation toward online learning. InSight: A Collection of Faculty Scholarship, 2, 70-80.

Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205-222.

Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating: The key to Teaching and Learning Online (3rd ed.) London: Routledge.

Smith, M. (2003). Jean Lave, Etienne Wenger and communities of practice. http://infed.org/mobi/jean-lave-etienne-wenger-and-communities-of-practice/

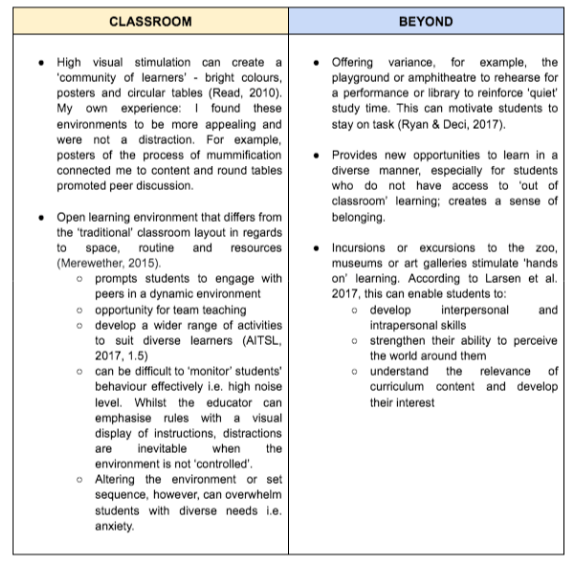

ARTICLE 6 – CLASSROOM AND BEYOND

I believe that students’ capacity to involve themselves in effortful learning is influenced by the environment in which it takes place.

Explore examples of programs ‘beyond’ the classroom: scienceworks, Sydney Opera House, Chau Chak Wing Museum

Image 1 retrieved from: Read, M. A. (2010). Contemplating design: Listening to children’s preferences about classroom design. Creative Education, 1(2), 75.

Image 2 retrieved from: Mooreco inc. (2019). 5 colors in the classroom that will boost active learning. https://blog.moorecoinc.com/5-colors-in-the-classroom-that-will-boost-active-learning

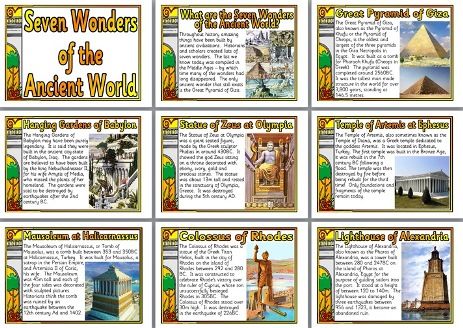

Image 3 retrieved from: Pinterest. (n.d). History Teaching resource. https://i.pinimg.com/564x/1a/0f/95/1a0f95e1cd047b88bc1828147ea16cb6.jpg

Image 4: poster I created and put in the classroom during my recent placement

REFERENCES

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2017). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/standards

Larsen, C., Walsh, C., Almond, N., & Myers, C. (2017). The “real value” of field trips in the early weeks of higher education: the student perspective. Educational Studies, 43(1), 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2016.1245604

Merewether, J. (2015). Young children’s perspectives of outdoor learning spaces: What matters?. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 40(1), 99-108. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911504000113

Read, M. A. (2010). Contemplating design: Listening to children’s preferences about classroom design. Creative Education, 1(2), 75.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications

ScienceWorks. (2022). Exhibits. https://scienceworksmuseum.org/exhibits-activities/

Sydney Opera House. (2022). Schools Performances, workshops, tours, digital learning, in-school residencies and work experience. https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/learn/schools.html

University of Sydney. (2022). Secondary Programs. https://www.sydney.edu.au/museum/education/secondary.html

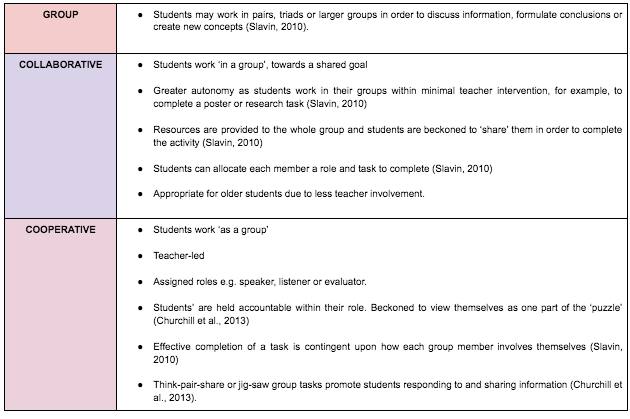

ARTICLE 5 – GROUP, COLLABORATIVE AND COOPERATIVE LEARNING SPACES

Within interactive learning spaces, students are granted opportunities to ‘grapple’ with content as a ‘community of learners’, developing valuable intrapersonal and interpersonal skills (Smith, 2003, Johnson et al., 1994). It is insufficient for educators to simply “transmit knowledge” (Bada & Olusegun, 2015, p.66) as students must be encouraged to develop social/cognitive skills through interaction. I have often viewed group, collaborative and cooperative learning spaces as terms synonymous with one another, however, they take different forms.

Clipart Library. (2019). Cooperative Learning Cliparts. http://clipart-library.com/image_gallery/n1539329.jpg

CHARACTERISTICS OF EACH LEARNING SPACE

Example of cooperative group learning:

Let’s Teach. (2020, October 14). What is the Jigsaw Method. . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JS6R0kq6PyU

From personal experience, establishing such learning without a specific intention or considering the environment in which it takes place ultimately leads to disengagement (Lund & Jolly, 2010).

REFERENCES

Bada, S. O., & Olusegun, S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66-70. DOI: 10.9790/7388-05616670

Churchill, S., Godinho, S., Johnson, N. F.; Keddie, A., Letts, W.; Lowe, K.; Mackay, J.; McGill, M.; Moss, J.; Nagel, M.; Shaw, K.; Vick, M. (2013). Teaching: Making a difference (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Holubec, E. J. (1994). The nuts and bolts of cooperative learning. Interaction Book Company.

Let’s Teach. (2020, October 14). What is the Jigsaw Method. . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JS6R0kq6PyU

Parsons, C. S. (2016). “Space and Consequences”: The Influence of the Roundtable Classroom Design on Student Dialogue. Journal of Learning Spaces, 5(2), 15-25.

Prichard, J. S., Bizo, L. A., & Stratford, R. J. (2006). The educational impact of team‐skills training: Preparing students to work in groups. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(1), 119-140.

Slavin, Robert E. (2010). Co-operative learning: what makes group-work work?. In Hanna Dumont, David Istance and Francisco Benavides (eds.), The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-9-en

Smith, M. (2003). Jean Lave, Etienne Wenger and communities of practice. http://infed.org/mobi/jean-lave-etienne-wenger-and-communities-of-practice/

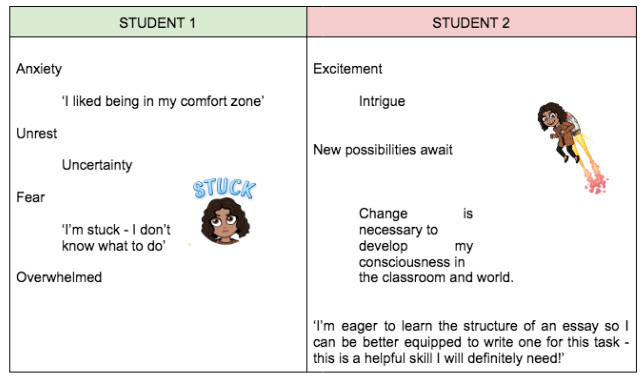

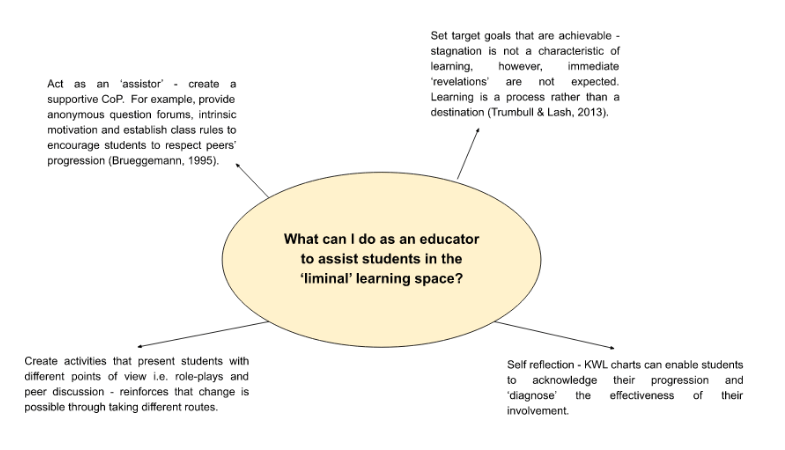

ARTICLE 4 – THE LIMINAL LEARNING SPACE

“Real learning requires stepping into the unknown, which initiates a rupture in knowing” (Schwartzman, 2010, p.38)

This ‘rupture’ underpins the ‘liminal’ learning space. Learners are beckoned to accept that they are within the unknown and untether themselves from prior understandings. In order for change to be ‘transformative’ and ‘progressive’, learners experience a “deep, structural shift in…thought, feelings and actions…a shift of consciousness that dramatically and irreversibly alters our way of being in the world” (O’Sullivan et al., 2022, p.11).

TEDx Talks. (2019, August 22). Liminal Spaces | Sarah Sawin Thomas | TEDxLincoln. . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWlKLhJW_P8

Ross (2011) views this process as ‘re-authoring’ and I am inclined to agree given that being within the liminal prompts learners to critically reflect upon cognitive processes and establish themselves in the post-liminal with new insights.

Learners can react differently within the liminal space through being confronted with new concepts and skills to develop.

These practices create an environment whereby critical reflection and questioning of ‘normalities’ is not only supported by actively encouraged (Land et al., 2014).

Personally, I have been within the liminal space as I progressed from Stage 5 to 6 in High School or transferred courses at University. Support and provision of a ‘safe space’ was crucial to navigate the ambiguity created by life’s uncertainties and progress without overwhelming pressure to be ‘transformed’ instantly.

REFERENCES

Brueggemann, W. (1995). Preaching as reimagination. Theology Today, 52(3), 313-329.

Land, R., Rattray, J. & Vivian, P. (2004). Learning in the liminal space: a semiotic approach to threshold concepts. High Educ 67, 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9705-x

O’Sullivan, E. (2002). The project and vision of transformative education. In E. O’Sullivan, A. Morrell, & A. O’Connor (Eds.), Expanding the boundaries of transformative learning (pp. 1–12). New York: Palgrave.

Schwartzman, L. (2010). Transcending disciplinary boundaries: A proposed theoretical foundation for threshold concepts. In R. Land, J. Meyer, and C. Baillie, (Ed.s), Threshold concepts and transformational learning. (21-44). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers

TEDx Talks. (2019, August 22). Liminal Spaces | Sarah Sawin Thomas | TEDxLincoln. . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWlKLhJW_P8

Trumbull, E., & Lash, A. (2013). Understanding formative assessment: Insights from learning theory and measurement theory. San Francisco: WestEd.

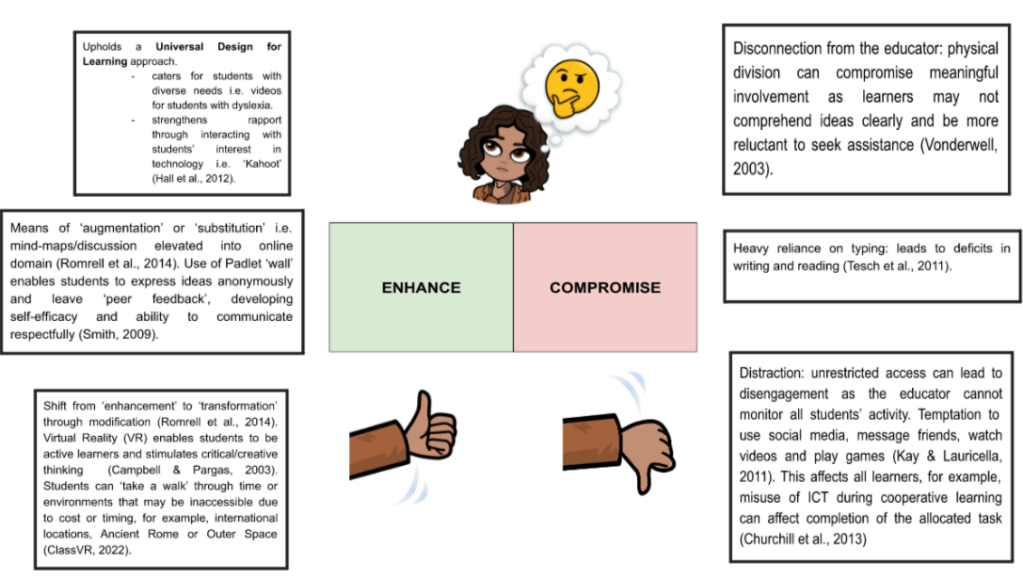

ARTICLE 3 – THE ONLINE LEARNING SPACE

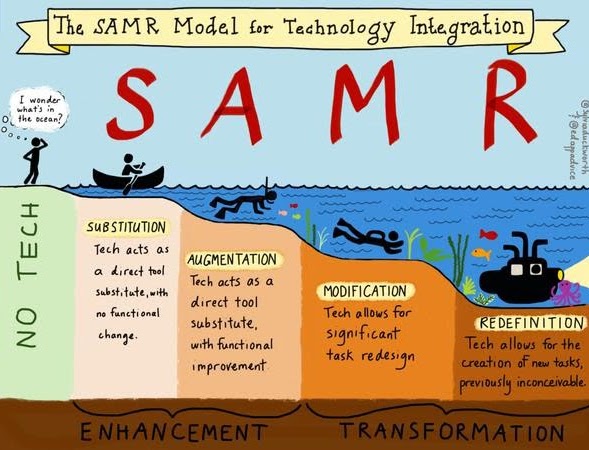

Considering the “ubiquity and pervasiveness of digital technologies within contemporary society” (Framroze, 2017, p.2), it is no surprise that it is used as a tool within the realm of education to assist and enhance learning.

It can act as a catalyst, promoting excitement and limiting disengagement through providing variation from the traditional ‘pen and paper’ learning form. However, it can be a direct source of disengagement due to its endless nature. Educators and learners must interact with ICT purposefully and consider its effect within the teaching and learning cycle (Hofmann, 2002).

Explore Virtual Reality Resource – ClassVR

Anita Vyas. (2018). Active Learning with Kahoot!. https://venturebeat.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/kahoot.png?fit=1132%2C601&strip=all

Auburn School Department. (2022). SAMR Model. https://cdn5-ss20.sharpschool.com/UserFiles/Servers/Server_219555/Image/Departments/Technology%20Team/Tech%20Tools%20for%20Teachers/SAMR%20Model/SAMR%20Model%20Technology.jpg

Sarah Fielding. (2020). Padlet . https://i0.wp.com/generic.wordpress.soton.ac.uk/digital-learning/wp-content/uploads/sites/321/2020/04/padlet-types.png?resize=755%2C428

REFERENCES

Campbell, A. B., & Pargas, R. P. (2003). Laptops in the classroom. ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 35(1), 98-102. https://doi.org/10.1145/792548.611942

Churchill, S., Godinho, S., Johnson, N. F.; Keddie, A., Letts, W.; Lowe, K.; Mackay, J.; McGill, M.; Moss, J.; Nagel, M.; Shaw, K.; Vick, M. (2013). Teaching: Making a difference (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

ClassVR. (2022). VR in Education for Ages 14 to 16 years. https://www.classvr.com/au/

Framroze, M. (2017). Self-spectacle online: The construction and representation of identity in contemporary digital culture. UCLA.

Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (Eds.). (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical applications. Guilford press.

Hofmann, D.W. (2002). Internet-based distance learning in higher education. Tech Directions, 62(1), 28 – 32.

Kay, R., and Lauricella, S. (2011). Unstructured vs. Structured Use of Laptops in Higher Education. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 10, 33-42.

Romrell, D., Kidder, L., & Wood, E. (2014). The SAMR model as a framework for evaluating mLearning. Online Learning Journal, 18(2). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/183753/.

Smith, M. (2003). Jean Lave, Etienne Wenger and communities of practice. http://infed.org/mobi/jean-lave-etienne-wenger-and-communities-of-practice/

Tesch, F., Coelho, D., and Drozdenko, R. (2011). The Relative Potency of Classroom Distractors on Student Concentration: We have met the enemy and he is us*. Proceedings of ASBBS, 18(1), 886-894.

Vonderwell, S., Liang, X., & Alderman, K. (2007). Asynchronous discussion and assessment in online learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 39(3), 309-328.

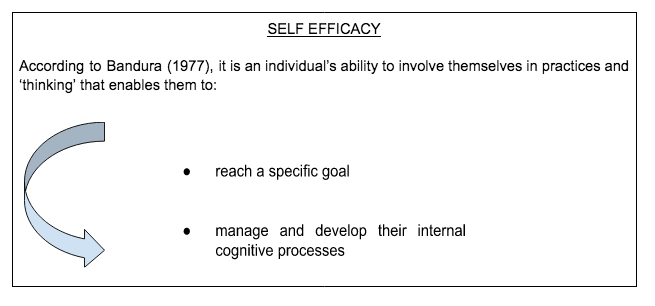

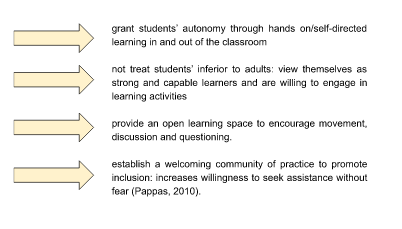

ARTICLE 2 – THE PERSONAL LEARNING SPACE

Learning is a lifelong process, intrinsically connected to all human practices and therefore “when we fail to take control of our education, we fail to take control of our lives” (Hayes, 1998, p.14).

Churchill et al. (2013) associate the term ‘learner’ with notions of ‘agency’ and ‘autonomy’, positioning learning as a student-centred ‘activity’. Within the ‘personal learning space’, students’ must be granted an element of control in order to reconnect with and develop their internal processes, feel a part of the ‘community of practice’ and develop their self-efficacy.

The Education Hub. (2019, August 29). Self Efficacy Animation. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7GbHIZBRWY

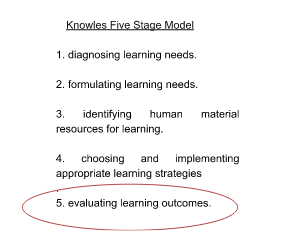

Learners’ participate in an activity, develop their interest, commit to it and view ‘set-backs’ as tasks yet to be mastered rather than disappointments (Bandura, 1977). Whilst the provision of extrinsic motivation can motivate learners to achieve goals, it does not aid in strengthening their self-efficacy as it can distract them from investing their time into continuous, effortful learning (Pew, 2007). I believe it is critical to encourage learners to be ‘proactive’ rather than entirely ‘reactive’ (Knowles, 1975).

Opennaurki. (2020). Intrinsic vs Extrinsic Motivation: How To Stay Motivated All The Time. https://i2.wp.com/d3d2ir91ztzaym.cloudfront.net/uploads/2020/11/Intrinsic-vs-Extrinsic-Motivation.png?resize=696%2C305&ssl=1

How? The ‘personal’ learning space at Candlebark School invited me to consider how I, as an educator, can:

SBS The feed. (2015, March 27). John Marsden’s Happy School. [Video]. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FuIyOZ2jHlY

It is also crucial to promote self-reflection, for example, the use of a KWL chart (Churchill et al., 2013) as students consider their involvement in activities, their attitude and response, and take gradual steps to achieve goals (Merriam & Caffarella, 1991).

The development of my ‘personal’ learning in EDFD459

REFERENCES

Bandura, A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review. 84 (2): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Churchill, S., Godinho, S., Johnson, N. F.; Keddie, A., Letts, W.; Lowe, K.; Mackay, J.; McGill, M.; Moss, J.; Nagel, M.; Shaw, K.; Vick, M. (2013). Teaching: Making a difference (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Hayes, C. (1998) Beyond the American Dream. Lifelong learning and the search for meaning in a postmodern world, Wasilla: Autodidactic Press.

Knowles, M. (1975). Self-Directed Learning. A guide for learners and teachers. Englewood Cliffs: Cambridge.

Merriam, S. B. and Caffarella, R. S. (1991). Learning in Adulthood. A comprehensive guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pappas, P. (2010). The Reflective Student: A Taxonomy of Reflection (Part 2). http://peterpappas.com/2010/01/reflective-student-taxonomy-reflection-.html

Pew, S. (2007). Andragogy and Pedagogy as Foundational Theory for Student Motivation in Higher Education. Student Motivation, 2, 17-18.

ARTICLE 1 – LEARNING TO LEARN ONLINE

Greenhow et al. (2022) note that the rise of COVID-19 greatly impacted the form in which learning takes place, being that ‘face to face’ became ‘screen to screen’. Despite presenting opportunities to learn in a new manner, Martin et al. (2020) suggest that a lack of familiarity with online learning can decrease learner engagement as ‘traditional’ practices may not effectively support learners in different contexts. It is vital to consider Salmons’ ‘Five Stage Model’ and critically reflect upon how educators and students play a pivotal role in facilitating effective, inclusive learning in the online domain. This model understands online learning as a gradual process, involving “intricate and complex interaction between neural, cognitive, motivation, affective and social processes” (Azevedo, 2002, p.31). These processes work together in a synchronous manner in order to establish an online learning space reflective of an inclusive ‘community of practice’ (Greenhow et al., 2022). Such communities are created through educators and students engaging in collective learning that encourages active communication and participation (Smith, 2009). Thus, consideration of ‘netiquette’ is crucial as progression within each stage and the development of all the aforementioned processes is contingent upon establishing a safe, respectful online environment (Teaching Online, 2014).

Dr R. Yeap. (2021, August 1). Salmon 5-stage model (by Professor Gilly Salmon) [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ckzlnXFncNo

Gilly Salmon. (2022). The Five Stage Model.

This is of particular importance with regard to involvement in Stage 2, ‘online socialisation’, as learning is not an isolated, passive process. It requires individuals working together, ‘expressing’ themselves and their understanding in order to strengthen their self-awareness and processes as an online learner (Salmon, 2011). The establishment of a welcoming online community of practice has motivated me to contribute to both written and verbal discussion, progressing from Stage 1 to 2 (Salmon, 2011). As a student, I acknowledged how it was critical for the educator to encourage rather than force direct communication, ultimately ‘creating’ invested learners.

REFERENCES

Azevedo, R. (2002). Beyond intelligent tutoring systems: Using computers as METAcognitive tools to enhance learning?. Instructional Science, 30(1), 31-45. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1013592216234

Dr R. Yeap. (2021, August 1). Salmon 5-stage model (by Professor Gilly Salmon) [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ckzlnXFncNo

Framroze, M. (2017). Self-spectacle online: The construction and representation of identity in contemporary digital culture. UCLA.

Gilly Salmon. (2022). The Five Stage Model. https://www.gillysalmon.com/uploads/5/0/1/3/50133443/1617139.png?515

Greenhow, C., Graham, C. R., & Koehler, M. J. (2022). Foundations of online learning: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 131-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2090364

Martin, F., Stamper, B., & Flowers, C. (2020). Examining Student Perception of Readiness for Online Learning: Importance and Confidence. Online Learning, 24(2), 38-58. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1260328

Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating: The key to Teaching and Learning Online (3rd ed.) London: Routledge.

Smith, M. (2003). Jean Lave, Etienne Wenger and communities of practice. http://infed.org/mobi/jean-lave-etienne-wenger-and-communities-of-practice/

Teaching Online. (2014). Course netiquette and guidelines. https://leocontent.acu.edu.au/file/ccbe60fc-4a3c-4a2c-a80e-286a4946a9f3/1/html/ote_2_30.html